Candidates: Are you interviewing and need support?

Every week we gather the greatest and latest HR news, articles, and insights, compiling them here in a weekly roundup. In this week's roundup we examine why so many new hires fail, predicting employee turnover, and some problems with the "hire fast, fire fast" philosophy. We'll also take a look at where things can go wrong in unstructured interviews, as well as strategies for engaging remote workers.

Ouch, 50% Of New Hires Fail! 6 Ugly Numbers Revealing Recruiting’s Dirty Little Secret

Dr. John Sullivan, ERE Media

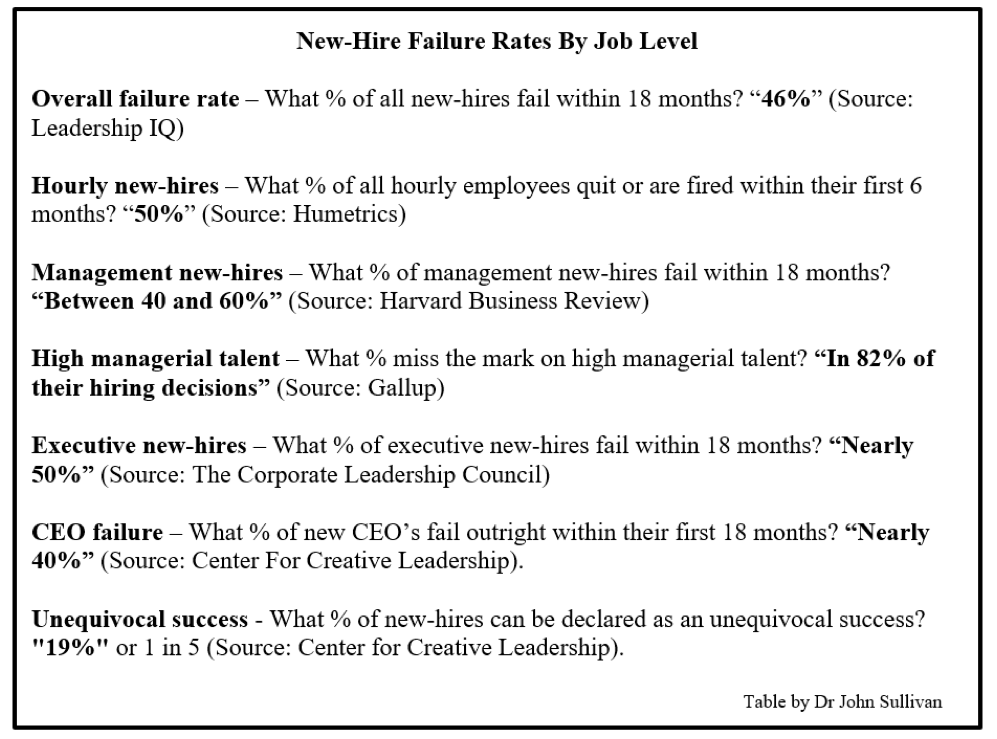

“The recruiting process often has a failure rate of 50%,” John Sullivan begins. “And that astonishing failure rate occurs at every job level, from hourly employees, to managers, and even at the executive level.” He summarizes the findings of several studies in this handy table:

Clearly something is going awry. Sullivan lists 6 of the most pronounced reasons things are going wrong:

- No measurement of the cost of a bad hire. Executives lead the charge on change when there is a clear, measured impact on revenue. But since the precise business cost of a bad hire is never quantified, holes in the process are never confronted.

- Process design isn’t scientific. “Almost all corporate recruiting processes are designed based on past practices or intuition,” Sullivan explains. “Without using process reengineering principles, it is unlikely that recruiting results will improve.”

- Intuition rather than data-based decision-making. “I have found that over 75 percent of the decisions made during most corporate recruiting processes are made by humans relying on their own intuition, rather than data,” Sullivan says.

- Process updates are a hodgepodge. Rather than redesigning the process from the ground up, pieces of it are selectively removed, modified, and added when a new vendor comes along or a major issue arises.

- Hiring failure rates and quality of hire are not even measured. Without measuring hiring failure rates, root causes cannot be addressed. By the same token, hiring successes cannot be duplicated.

- HR is not a data-driven function. If the rest of HR isn’t data-driven, the recruiting process certainly won’t be.

Putting numbers to names is critical for measuring the overall success of a function - and figuring out where things go wrong. “Work with the CFO’s office to calculate the dollar impact of each bad, weak, or top performer/innovator new hire,” Sullivan concludes. “Because like most things in business, recruiting is really all about the money.”

HV Analysis:

Sullivan hits the nail on the head with this one, particularly with point #4. When confronted with the latest and greatest shiny tech solution, many TA departments layer it onto their existing process - adding bloat rather than removing it. For example, say you purchase a fancy new video interviewing software. It has phenomenal customer support, excellent security, and industry-leading uptime. A pretty great product, right? Used correctly, it has the potential to decrease time to fill, increase quality of hire, and improve the candidate experience. But if it’s just added as an extra step after a phone screen, the process gets longer, not shorter. I think we can also group #4 with #6. Without a solid foundation of data to work from, any attempt at process change is just throwing mud at a wall and hoping it sticks.

Predicting Turnover: The Top 5 Reasons Employees Leave

Dan Harris, TalentCulture

To get a better grasp of what drives turnover, Dan Harris analyzed a dataset of more than 97,000 survey respondents. In his analysis, he found five key indicators of employee turnover.

- Lower Job Satisfaction. A number of things could drive low satisfaction, but when it is low, employees are more likely to turnover.

- Unmet Individual Needs. Health, work-life balance, and personal development are all individual needs that, if not met, make employees more likely to turnover.

- Future Misalignment. If an employee cannot imagine themselves in the organization’s future, they are more likely to turnover.

- Poor Team Dynamics. If employees are unsure about the efficacy of their fellow team members, they are a retention risk.

- Lower Intentions to Stay. “When employees indicate that they’re unsure if they’ll stay with the organization — both in the short term or during tough times — they’re more likely to become a retention risk,” Harris explains.

All the indicators above seem fairly intuitive - Harris provides a little more insight into trends in the data set. “Group-level differences suggest that it doesn’t take as much for new hires or highly tenured employees to term, whereas it takes more uncertain or negative perceptions for moderately tenured employees to term,” Harris says. In other words, the newest hires and most tenured are most likely to quit.

Another insight: it takes more to make employees at smaller organizations leave than it does for those in larger organizations.

“Although turnover is complex, a “one size fits all” approach to preventing or responding to employee turnover just doesn’t work,” Harris concludes. “It is imperative to collect and analyze exit data using reliable tools, a strong methodology, and a commitment to implementing insights gathered from those data.”

HV Analysis:

Sometimes analyzing data doesn’t really tell you anything you don’t already know - but it does provide more solid evidence for what you suspect, and can be useful in identifying patterns. It seems fairly obvious that employees with “low intentions to stay” would be more apt to leave - but I think we can identify a trend within Harris’ five indicators.

Simply put, Harris’ indicators come about as the result of outdated management strategies. Companies that care for their employees, give frequent feedback, and provide opportunities to grow and advance will probably have higher job satisfaction and intent to stay within the workforce.

It’s no coincidence, then, that smaller companies (which have an easier time providing those things) generally have more loyal employees.

Nobody Gets a Great Idea When They’re Being Chased by a Lion

John Hollon, Fistful of Talent

The “hire slow, fire fast” adage is pervasive in entrepreneurial circles, particularly those that are pushing for swift innovation. But, as Mark Nathan (CEO of Zipari), so aptly explains: “Nobody ever comes up with a brilliant idea while they’re being chased by a lion.”

“In a culture where employees are so preoccupied with daily survival that they simply can’t focus on anything else, both people AND innovation get strangled in the process,” John Hollon explains. “When everyone comes to work in fear of losing their job, nobody is thinking about how to do things better.”

He illustrates this with the example of Jeff Jones, who recently joined (and resigned from) Uber. When Jones left, he said: “The beliefs and approach to leadership that have guided my career are inconsistent with what I saw and experienced at Uber.”

Company culture is built with a consistent support and daily guidance for your workforce. “If they truly believe you want them to be innovative, and will reward them for it, they’ll give you good stuff that reinforces the organization’s positive spirit,” Hollon concludes.

HV Analysis:

It seems like lately the startup mindset of “grow or die” has fed into a different, unprecedented approach to hiring and firing. Rather than the old adage “hire slow, fire fast,” we seem to be experiencing the adoption of a new paradigm: “hire fast, fire fast.”

Either way, Hollon’s (and Nathan’s) point holds. When the order of the day is survival, it is very difficult to innovate. Maybe instead of creating a company culture that people join, we should focus on creating a culture that people can add to.

The Utter Uselessness of Job Interviews

Jason Dana, The New York Times

“Employers like to use free-form, unstructured interviews in an attempt to “get to know” a job candidate,” Jason Dana begins. “But interviewers typically form strong but unwarranted impressions about interviewees, often revealing more about themselves than the candidates.”

For example, in 1979, the University of Texas Medical School at Houston was required to increase its incoming class size by 50 students. The 50 students who reached the interview phase of the application process were all rejected - despite having identical honors and the same academic performance of those already admitted. “The judgment of the interviewers, in other words, added nothing of relevance to the admissions process.”

The issue is that most people have no difficulty creating a coherent narrative from disparate information. “People can’t help seeing signals, even in noise,” Dana says.

In order to combat this, Dana offers two options:

- Structure interviews.

- Use Interviews to Test Job-Related Skills.

He concludes: “Unstructured interviews aren’t going away anytime soon. Until then, we should be humble about the likelihood that our impressions will provide a reliable guide to a candidate’s future performance.”

HV Analysis:

Remember a few articles ago when Dr. John Sullivan presented that 50% of new hires fail? This piece from Jason Dana digs into one of the specific reasons why. His piece has some other examples that I didn’t have the space to summarize, so you should definitely check it out in full. It’s great that the New York Times is giving attention to one of the biggest sources of bias in hiring. Dana presents the problem perfectly: when we are presented with gaps in information, we fill in the blanks to create our own cohesive narrative. And unfortunately, that cohesive narrative almost always pulls unconscious bias into the mix. Video interviews, coincidently, are structured. It is because all candidates are asked the exact same questions that a team of I/O Psychologists can build a predictive model of performance.

4 Best Strategies to Keep Your Remote Team Engaged

Jose Bautista, Workology

Remote work has been shown to improve productivity and attract a larger talent pool - but it’s not always easy to engage remote team members long-distance. Jose Bautista provides four strategies to engage remote workers:

- Be Polite. Simple “thank yous” and “hellos” are easy ways to make remote team members feel appreciated and valued.

- Empower Individuals. Setting goals not only provides a framework around which to evaluate performance, it also sets people up to go above and beyond.

- Keep Up Communication. It is easy to fall out of a communication cadence with remote team members - establish consistent touch points.

- Provide Some Great Benefits. By providing the option of remote work, you’ve already taken a huge step toward engaging the workers inclined to take this option.

HV Analysis:

IBM recently mandated that all its remote workers relocate to cities where they can come to work onsite. The goal: the innovation-driving “water cooler effect.” While remote workers are consistently shown to be more productive, this does not necessarily hold for innovation. In the realm of new idea synthesis, impromptu meetings and conversations around the water cooler reign king.

This is why point #3 is so important. When remote workers are engaged with consistent communication, it stands to reason that they will be more likely to reach out when a new idea strikes. Of course, this also holds for predetermined meetings, where they will feel more comfortable speaking their mind.