Candidates: Are you interviewing and need support?

Hiring for "cultural fit" is a hot topic in the world of talent acquisition. But for all its buzz, we seem to get monthly reminders that it's not all it's cracked up to be. What began as a benign attempt to increase productivity and cohesiveness in the workplace has (for many) devolved into an excuse for exclusive hiring practices.

Where did the notion of "cultural fit" come from? When did "cultural fit" become "cultural snobbery"? And how can you reframe company culture in a way that increases productivity and fosters innovation? These are all good questions that deserve good answers. Here's my take:

If it fits it fits - or does it?

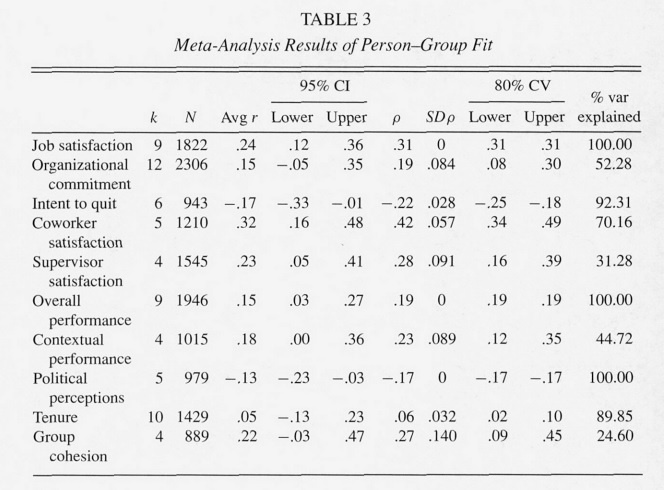

The hubbub around cultural fit stems from a meta-analysis conducted in 2005 by Amy Kristof-Brown at the University of Iowa College of Business, which found that employees who “fit well with their organization, supervisor, and group of coworkers”:

- Were more satisfied with their job.

- Were more committed to the organization.

- Had less intent to quit.

- Performed better overall.

Sounds pretty great, right?

Unfortunately, many who reference this piece do not read past this table...

...and inadvertently ignore a conundrum the authors themselves struggled with.

In their conclusions on future research pursuits, the authors state that: “despite the acknowledgement that multiple conceptualizations of fit exist, there has been surprisingly little research focused on validating multidimensional approaches.”

In other words, every study they investigated had a different definition of "cultural fit" - so quantifying exactly what qualifies as “fit” is a serious confound in any attempt to analyze the data set.

And in the “Limitations and Strengths” section of the analysis, they discuss a colleague's 1991 findings that “nearly every study reviewed contained methodological flaws that seriously threaten the interpretability of the results obtained.”

So the primary driver of discussions on cultural fit, the parent piece of academic evidence in favor of hiring for “fit,” is imperfect. This is not to say it is worthless - those that think they “fit” within a company culture probably tend to be happier. But even so - is this a case of the chicken or the egg?

The Chicken or the Egg: Cultural Fit's Causality Dilemma

Most talent acquisition practitioners advocate hiring for cultural fit due to the four reasons listed above. But what if “cultural fit” was a result of those four data points, rather than the cause? Let’s look at a silly example to analyze this:

Hugh is a fairly average financial analyst. He’s a solid worker, gets along well with most people, and has a couple hobbies. When his family relocated to another city, he had no trouble finding work: every managerial reference gave his work ethic high marks, and he has a skill in high demand.

With several options available to him, he selects the job that gives him the most time off to spend with his family, provides good health benefits, and matches his 401k 1:1 up to 5%.

A year later, he is still satisfied with his job. Since his place of work lets him spend a good deal of time with his family, he is committed to the organization. And with good health benefits, why would he want to quit? As a result of the low stress and many benefits his work provides, he performs better overall.

Sound familiar? But let’s not stop there:

Satisfied with his job, Hugh agrees with his employer’s branding initiatives. Since he’s committed to his organization and unlikely to quit, he gets along well with his fellow employees. And as a solid performer, his supervisor loves him.

Now, when recruiters talk about who they want to recruit, they consistently refer to Hugh as a "great cultural fit."

From “Culture Fit” to “Culture Snobbery”

So which comes first? The fit? Or the success attributed to fit?

The unfortunate fact of the matter is that no one knows (or rather, it often goes both ways, but is only attributed in a single direction). And instead of throwing out “cultural fit” as a potentially flawed recruitment strategy, it tends to be used in the worst possible way: as an excuse.

See, it’s illegal when applicants are screened out based on age, race, and gender - but it’s not illegal to screen them out based on culture. If company’s “culture” just so happens to be young, white, and male, what’s to keep them from “hiring for culture” and screening out women and minorities?

This is not to say these sorts of hiring decisions are being made explicitly. Recruiters are responsible for sifting through huge amounts of data on a daily basis - it's human nature that they unconsciously select those most like themselves.

Age, race, and gender play a huge role in the experiences we are exposed to, and as a result, the cultures we identify with. And unfortunately, when “hiring for culture,” many organizations forget that they are revenue generating businesses and not schoolyard social groups.

This is not to say a company culture must be defined solely by the collective experience of its current employees. Many would argue that values like hard work, critical thinking, and openness to communication are the best metrics around which to base a company culture.

But hold on a second. Values like hard work? Critical thinking? Open communication with superiors? Is there a single business that doesn’t want these things in its employees? If a company culture is based around values deemed universally valuable, is it really necessary, or even correct, to call it a “culture”? I seriously doubt it.

So at this point I think it would be fair to say that a “company culture” is either:

- A set of organizational values that are inevitably affected by the race, gender, and age of its constituents, or:

- A set of organizational values that are transferable to literally any other organization.

In either case, where’s the value in hiring for cultural fit?

From “Culture Fit” to “Culture Add”

In the article from Ere Media, Moving Past Culture Fit To “Culture Add”, the author Jody Ordioni makes the distinction between fitting in a culture and adding to it. And I think she's on to something.

In this case, the definition of “company culture” as laid out in point #1 makes sense - incorporating diverse groups, ideas, and points of view is something every company with the tiniest aspiration to innovation should desire. She goes on to talk about the “3 Es of culture add”: Employees, Employer brand, and Expectations. These “Es” are factors you need to consider when reframing a culture of exclusion as a culture of addition.

- Employees. Make clear to current employees that they will be working with diverse new team members. Show the productivity and revenue benefits of doing so.

- Employer brand. Make clear to potential applicants that your workplace welcomes and encourages cultural addition, rather than assimilation. Let each candidate know that they will be encouraged to add their unique worldview to the workplace.

- Expectations. Make clear to hiring managers and recruiters that there are expectations they’ll need to meet. Provide change management training to help them talk with diverse candidates and remove implicit bias.

Implementing Cultural Addition

As Jody Ordioni touched on, implementing cultural addition starts with identifying and hiring diverse talent. But giving recruiters and managers a vague set of hiring expectations without the proper toolset is a recipe for disaster (or worse: apathy).

To identify diverse talent, you need to start at the top of the hiring funnel. While recruiters (usually) don't screen out candidates based on irrelevant metrics like race and gender, the data they are initially presented with has a very real impact.

For example, Asian-looking names receive 20% fewer callbacks. And of course, there is the infamous study where "Emily" and "Greg" were 50% more likely to be called back than "Lakisha" and "Jamal." GPA and college pedigree are also pretty poor predictors of workplace performance.

In other words, the ability to add to a company’s culture is not something that can be discovered from a resume screen.

Most organizations use phone screens as the next step in the hiring process, but by this time it is often too late: the best “culture adds” have already been screened out. While it might be optimal to phone screen every candidate, this is far from practical.

Addition via Process Change

There are various tech solutions that can provide assistance if you're looking to identify cultural addition from the get-go.

We at HireVue have a justifiable bias toward on-demand video interviewing, but let me tell you why: with an on-demand video interview as the first step in the screening process, recruiters and hiring managers can ascertain "culture adds" from the very start. Note: like any solution, simply layering it over the existing process probably won't be much of a help. Harnessing the value of any shiny new TA solution requires fundamental process change.

Used in this way, on-demand video interviews provide the best of both worlds:

- They allow for quick screening of applicant pools. (These four companies hire in under a week).

- They give insight into each candidate’s ability to culturally contribute, not a set of numbers and irrelevant metrics.

It would be frivolous to say that transforming from a "culture fit" to a "culture add" mindset is easy, even with all the right tools and processes in place. It takes work, dedication, and buy-in from stakeholders throughout the hiring pipeline.

But in a world where innovation and outside-the-box thinking are key to long-term business success, creating a workplace that values each member's unique cultural addition is a tantalizing prospect - and one that should be taken seriously.